Are tornadoes increasing? Not really, the number has remained relatively constant. What is changing is that there are fewer days with tornadoes each year, but on those days there are more tornadoes, according to a NOAA report published today in the journal Science.

NOAA researchers looked at records of all but the weakest tornadoes in the United States from 1954 to 2013 for the study, “Increased variability of tornado occurrence in the United States.” They found that although there are fewer days with tornadoes, when a tornado does occur, there is increased likelihood there will be multiple tornadoes on that day. A consequence of this is that communities should expect an increased number of catastrophes, said lead author Harold Brooks, research meteorologist with the NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory.

“Concentrating tornado damage on fewer days, but increasing the total damage on those days, has implications for people who respond, such as emergency managers and insurance interests,” Brooks said. “More resources will be needed to respond, but they won’t be used as often.”

Why tornadoes are concentrating on fewer days is still an open question, Brooks said. The pattern may be connected to changes in weather and climate. More research involving climate and tornado scientists is needed.

The study also showed there is greater variability in the starting date of spring tornado season, with more early starts and late starts in recent years. From 1954 to 1997, 95 percent of the time tornado season started between March 1 and April 20. But in the last 17 years, this happened only 41 percent of the time.

Researchers note tornadoes differ from tropical cyclones or hurricanes in the North Atlantic because tornadoes can occur year round. In fact, tornadoes have occurred in the U.S. on every calendar day at some point during the past 60 years.

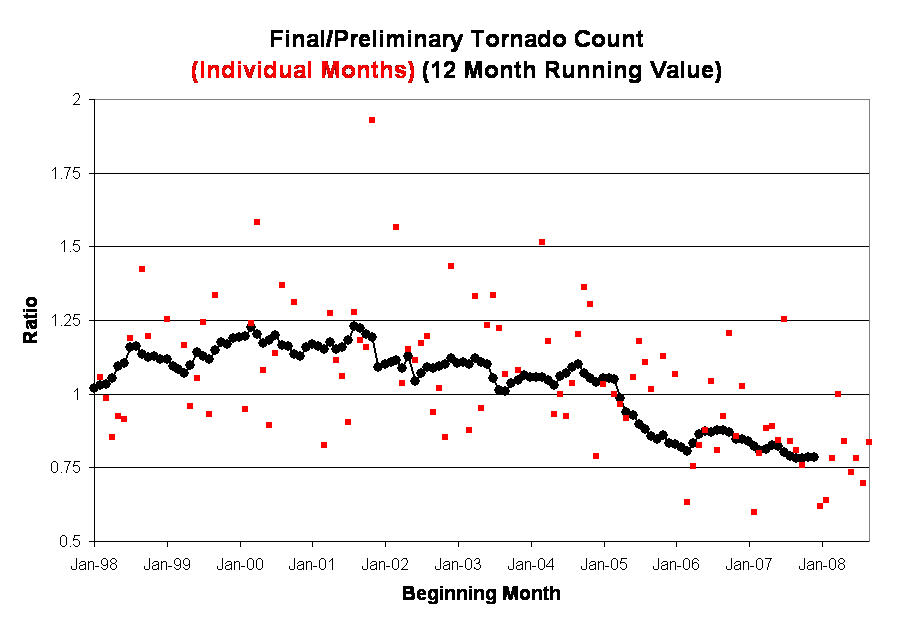

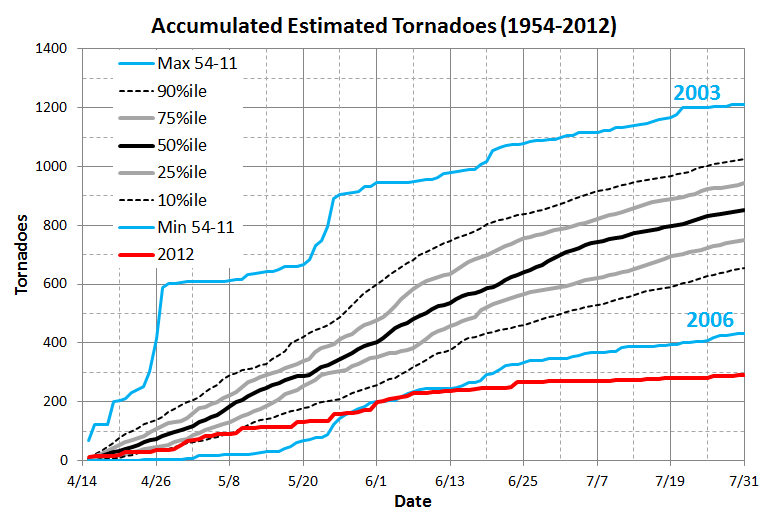

Recent experience illustrates the study’s findings of variability. The study looked at tornadoes rated EF1 or higher on the Enhanced Fujita Scale, a measure of the damage caused by tornadoes with categories from EF0 to EF5. From June 2010 to May 2011, there were 1,050 EF1 and stronger tornadoes, the most in any 12-month period on record. Shortly after that, the U.S. saw the fewest in a 12-month period, only 236 EF1 and stronger tornadoes occurred from May 2012 to April 2013. November of 2012 had no EF1 tornadoes, but November of 2013 had the sixth most on record, with 66. There have been a relative low number of tornadoes to date in 2014, with an estimated 800 tornadoes of all intensities reported through September, almost 400 tornadoes below what is considered a normal year.

The study’s results are a first step toward understanding the relationship between changing tornado activity and a changing climate. The next step will be for climate scientists and tornado researchers to work together to identify what specific large scale pattern variations in climate may cause, or are related to, clustering of tornado activity.

Co-authors of the study are Gregory Carbin and Patrick Marsh with the NOAA’s National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center.